Constraint Satisfaction Problem

Constraint Satisfaction Problems (CSP) use a factored representation of each state, with each state associated with a set of variables $(X)$, each variable containing a value from its domain $(D)$. The objective of the problem is to find the value for each of the variables that satisfy all the constraints(C) of the problem.

A CSP comprises of three components:

- Set of variables $(X) = \{ x_1, x_2, \ldots , x_n \}$.

- Set of domains $(D)$ belonging to each variable $\{D_1, D_2, \ldots , D_n \}$ where $D_i=\mathsf{domain}(x_i)$

- Set of constraints $(C)$ that specifies the valid combinations of values assigned to each variable.

In CSP, the order of a series of actions does not affect possible outcomes. Hence, CSP problems are commutative. Let us consider an algorithm to solve CSP.

Backtracking Search

One useful algorithm to solve CSP is the Backtracking Search. Let us try to represent the 4-Queen puzzle as CSP; first, we have to find a variable, the possible domain for each variable, and the constraint to solve.

We can describe the CSP as follows:

- Variables: { $x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4$}, where each $x_i$ represent the variable for $i^{th}$ column in $4 \times 4$ grid.

- For each variable $x_i$: $D_{x_i} = \{1,2,3,4\}$, $D_{x_i}$ represent the value of the row, i.e. each variable $x_i$ can possibly take a value of the row.

- Constraints: Let $\mathsf{noattack}(x_i,x_j)$ return True if the queen at $x_i$ cannot attack the queen at $x_j$, and False otherwise.

- $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_2)$

- $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_3)$

- $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_4)$

- $\mathsf{noattack}(x_2,x_3)$

- $\mathsf{noattack}(x_2,x_4)$

- $\mathsf{noattack}(x_3,x_4)$

We can specify the constraints fully for each $\mathsf{noattack}(x_i,x_j)$ in a huge truth table as seen in Table below:

Specifying constraints on a huge truth table

| $x_1$ | $x_2$ | $\mathsf{noattack}$ |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | False |

| 1 | 2 | False |

| 1 | 3 | True |

| 1 | 4 | True |

| 2 | 1 | False |

| … | … | … |

We aim to choose the values of all $x$ so that none of the queens in their respective positions can attack each other.

Backtracking Search Algorithm

We first consider a naive algorithm that does not check for variables’ consistency in assigning values to them. Algorithm 1 represents the naive Backtracking approach for CSP.

Algorithm 1 BacktrackingSearch $(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$

- if AllVarsAssigned$(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$ then

- $~~$if IsConsistent$(\mathsf{assign})$ then

- $~~~~$ return $\mathsf{assign}$

- $~~$else

- $~~~~$ return $\mathsf{failure}$

- $\mathsf{var}\gets$ PickUnassignedVar $(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$

- for $\mathsf{value}\in$ OrderDomainValue $(\mathsf{var},\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$ do

- $~~$ $\mathsf{assign}\gets\mathsf{assign}\cup(\mathsf{var}$ = $\mathsf{value})$

- $~~$ $\mathsf{result}\gets$ BacktrackingSearch $(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$

- $~~$if $\mathsf{result}$ != $\mathsf{failure}$ then return $\mathsf{result}$

- $~~$ $\mathsf{assign} \gets \mathsf{assign} \setminus(\mathsf{var}= \mathsf{value})$

- return $\mathsf{failure}$

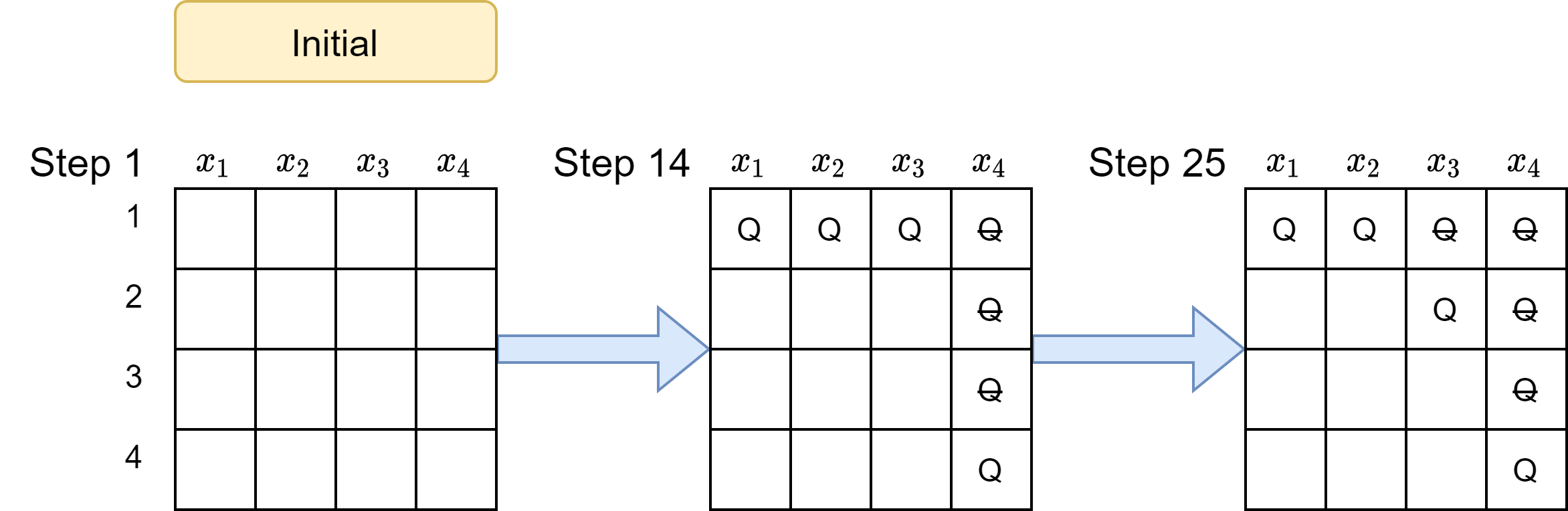

Let us try to execute Algorithm 1 step by step for the 4-Queen puzzle. Figure 1 represents the board overview of the backtracking algorithm to solve the 4-Queen puzzle.

|

|---|

| Figure 1: Board state at various steps of naive Backtracking Search. |

Let be the $i^{th}$ functional call and $j^{th}$ operation in that functional call. The execution of the algorithm goes as follows:

1.1 Pick variable $x_1$; 1.2 Set $x_1=1$

2.1 Pick variable $x_2$; 2.2 Set $x_2=1$

3.1 Pick variable $x_3$; 3.2 Set $x_3=1$

4.1 Pick variable $x_4$; 4.2 Set $x_4=1$

5.1 IsConsistent(assign)=False, thus backtrack; 4.3 Set $x_4=2$

5.1 IsConsistent(assign)=False, thus backtrack; 4.4 Set $x_4=3$

5.1 IsConsistent(assign)=False, thus backtrack; 4.5 Set $x_4=4$

5.1 IsConsistent(assign)=False, thus backtrack

4.6 Finished ‘for’ loop, thus backtrack; 3.3 Set $x_3=2$

4.1 Pick variable $x_4$; 4.2 Set $x_4=1$

5.1 IsConsistent(assign)=False, thus backtrack; 4.3 Set $x_4=2$

5.1 IsConsistent(assign)=False, thus backtrack; 4.4 Set $x_4=3$

5.1 IsConsistent(assign)=False, thus backtrack; 4.5 Set $x_4=4$

5.1 IsConsistent(assign)=False, thus backtrack

4.6 Finished ‘for’ loop, thus backtrack

$\cdots$

As shown in the above execution of Algorithm 1 for the 4-Queen puzzle, the main drawback of the algorithm is to check at the end if the assignment is consistent. It assigns a possible value to each of the four variables and then checks at the end if the assignment is consistent. If not, the algorithm changes the value of one variable and repeats. Therefore, Algorithm 1 would check for consistency with respect to all possible permutations of values $1$ to $4$ assigned to each of the four variables $x_1$ to $x_4$.

Improved Backtracking Search

To overcome the issue of Algorithm 1, a better approach would be for every time the algorithm has to assign a value to a variable, it first checks to ensure that the assigned value is consistent with the previous assignments. Therefore, the improved Algorithm 2 assigns a position to the queen only if another queen can not attack it.

Algorithm 2 BacktrackingSearch $(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$

- if AllVarsAssigned$(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$ then

- $\mathsf{var}\gets$PickUnassignedVar$(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$

- for $\mathsf{value}\in$ OrderDomainValue$(\mathsf{var},\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$ do

- $~~~~$if ValueConsistentWithAssignment $(\mathsf{value},\mathsf{assign},\mathsf{problem})$ then

- $~~~~~~~~$ $\mathsf{assign} \gets \mathsf{assign} \cup (\mathsf{var} = \mathsf{value})$

- $~~~~~~~~$ $\mathsf{result}\gets$ BacktrackingSearch$(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$

- $~~~~~~~~$ if $\mathsf{result}$ != $\mathsf{failure}$ then return result

- $~~~~~~~~$ $\mathsf{assign} \gets \mathsf{assign} \setminus (\mathsf{var}$=$\mathsf{value})$

- return $\mathsf{failure}$

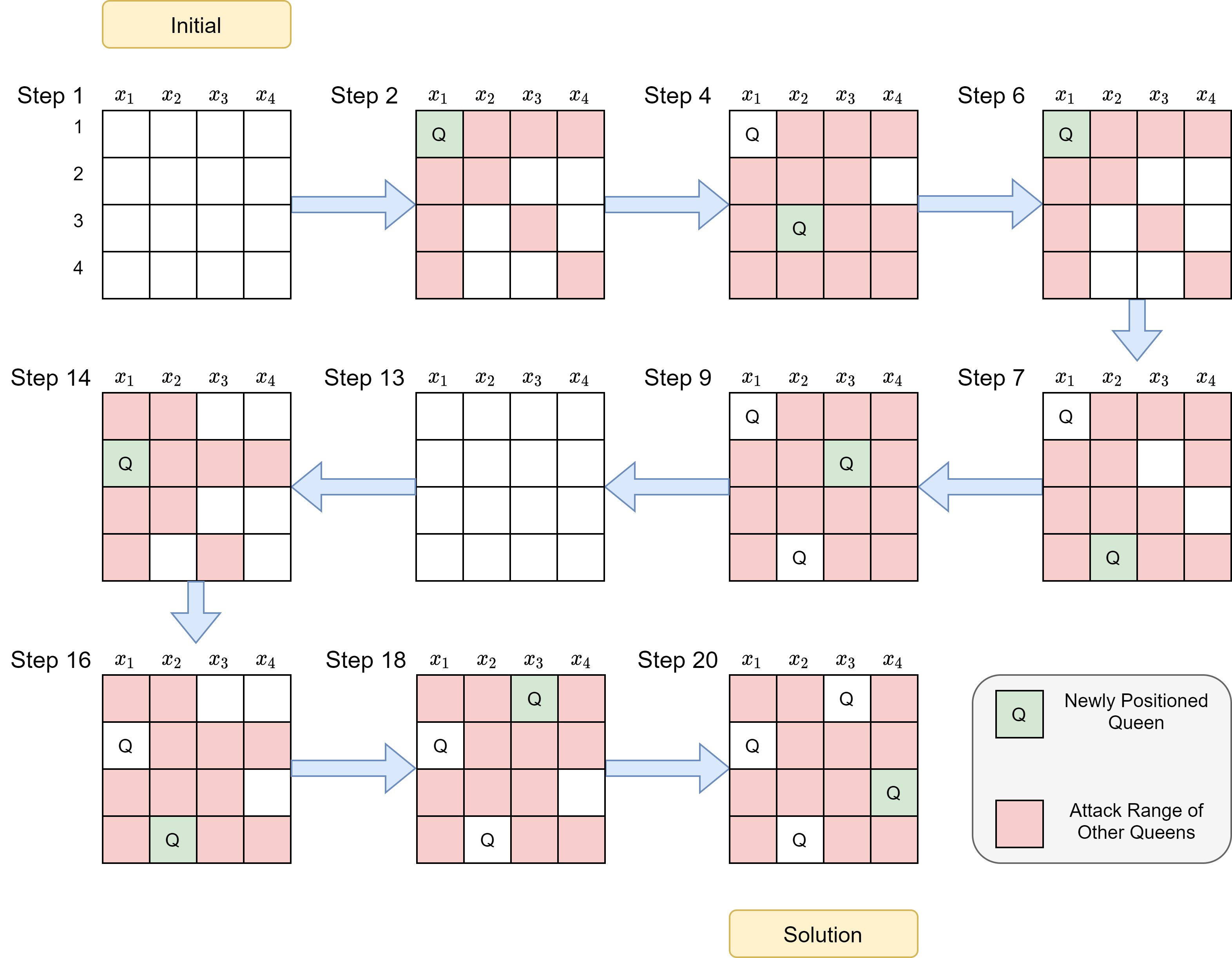

Let us try to execute Algorithm 2 step by step for the 4-Queen puzzle. Figure 2 represents the board overview of the backtracking algorithm to solve the 4-Queen puzzle.

|

|---|

| Figure 2: Board state at various steps of improved BacktrackingSearch |

The execution of the algorithm goes as follows:

1.1 Pick $x_1$; 1.2 Set $x_1=1$

2.1 Pick $x_2$; 2.2 Set $x_2=3$ as $\{1,2\}$ is attackable

3.1 Pick $x_3$; Return $\mathsf{failure}$ as $ \{1,2,3,4\}$ are attackable

2.3 Set $x_1=4$ as $ \{1,2\}$ is attackable and $\{3\}$ had been assigned

3.1 Pick $x_3$; 3.2 Set $x_3=2$ as $ \{1,3,4\}$ are attackable

4.1 Pick $x_4$

4.2 Return $\mathsf{failure}$ as $ \{1,2,3,4\}$ are attackable

3.3 Return $\mathsf{failure}$ as $ \{1,3,4\}$ are attackable and $\{2\}$ had been assigned

2.4 Return $\mathsf{failure}$ as $ \{1,2\}$ are attackable and $\{3,4\}$ had been assigned

1.3 Set $x_1=2$

2.1 Pick $x_2$; 2.2 Set $x_2=4$ as $ \{1,2,3\}$ are attackable

3.1 Pick $x_3$; 3.2 Set $x_3=1$ as $ \{2,3,4\}$ are attackable

4.1 Pick $x_4$; 4.2 Set $x_4=3$ as $ \{1,2,4\}$ are attackable

5.1 Return $assign$ because all variables are assigned

As seen from the execution of Algorithm 2, checking consistency every time a value is assigned to a variable improves efficiency, and we reach the goal state in fewer steps than with Algorithm 1.

Backtracking Search with Inference

Another idea to improve the efficiency of the Backtracking Search is that once the algorithm assigns a value to a variable $x_i$, it checks for all the constraints that $x_i$ appears to infer the restrictions on rest of the variables and avoid picking values that are not consistent with previous assignments and possible future assignments.

We have a new function, Infer$(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{var},\mathsf{assign})$, that outputs a set of assignments that can be inferred based on the constraints of the problem whenever a $\mathsf{value}$ is assigned to a variable. If it is inferred that we can not assign a value to all variables consistently, the function returns a $\mathsf{failure}$. In other words, the function helps to make inferences on what values other unassigned variables can take. In CSP-s, assigning a value to a variable could restrict the value other variables can take, which could propagate the restrictions to other variables. The Infer function aims to identify and use these restrictions to restrict the search space further.

Algorithm 3 represents the improved backtrack algorithm with inference.

Algorithm 3 BacktrackingSearch_with_Inference $(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$

- if AllVarsAssigned $(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$ then

- $\mathsf{var}\gets$ PickUnassignedVar $(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$

- for $\mathsf{value}\in$ OrderDomainValue$(\mathsf{var},\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$ do

- $~~~~$if ValIsConsistentWithAssignment$(\mathsf{value},\mathsf{assign})$ then

- $~~~~~~~~$ $\mathsf{assign}\gets\mathsf{assign}\cup(\mathsf{var}$ = $\mathsf{value})$

- $~~~~~~~~$ $\mathsf{inference}\gets$ Infer $(\mathsf{var},\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$

- $~~~~~~~~$ if $\mathsf{inference} \neq \mathsf{failure}$ then

- $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ $\mathsf{assign}\gets\mathsf{assign}\cup \mathsf{inference}$

- $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ $\mathsf{result}\gets$ BacktrackingSearch$(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{assign})$

- $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$if $\mathsf{result}$ != $\mathsf{failure}$ then return result

- $~~~~~~~~$ $\mathsf{assign} \gets \mathsf{assign} \setminus \{ (\mathsf{var} = \mathsf{value}) \cup \mathsf{inference} \}$

- return $\mathsf{failure}$

Below is the execution of Algorithm 3 for the 4-Queen problem:

1.1 Pick $x_1$; 1.2 Set $x_1=1$

1.3 $\mathsf{inference}$ returned as $\mathsf{failure}$, remove assignment $x_1=1$

1.4 Set $x_1=2$

1.5 $\mathsf{inference}$ returned as $\{x_2=4, x_3=1, x_4=3\}$

2.1 Return $assign$ because all variables are assigned

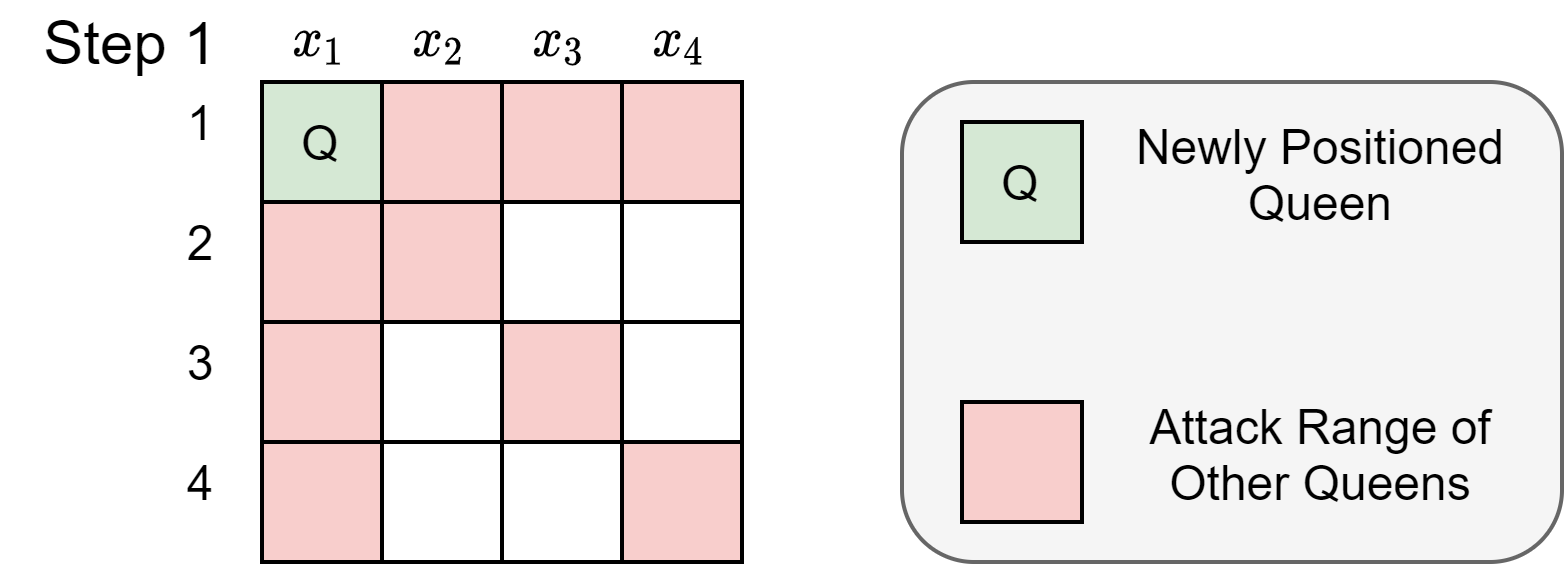

Inference Function Logic at Step 3

At step 3, because $x_1=1$, the inference function is able to deduce that the red squares in Figure 3 are within a queens attacking range, and no other queens can be placed there.

|

|---|

| Figure 3: Board state at various steps of improved BacktrackingSearch with Inference |

Then, the inference function looks at every constraint to infer restrictions on the rest of the variables.

Constraint 1: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_2)$

Observation from Figure 3 : $x_1=1 \Rightarrow x_2 \notin \{1,2\}$

Constraint 2: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_3)$

Observation from Figure 3 : $x_1=1 \Rightarrow x_3 \notin \{1,3\}$

Constraint 3: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_4)$

Observation from Figure 3 : $x_1=1 \Rightarrow x_4 \notin \{1,4\}$

Constraint 4: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_2,x_4)$

Because $x_2 \in \{3,4\}$,

If $x_2=3 \Rightarrow x_4=2$

If $x_2=4 \Rightarrow x_4=3$

Constraint 5: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_2,x_3)$

Deduction: $x_2 \in \{3,4\} \Rightarrow x_3 \notin \{3,4\}$

Deduction: $x_3 \notin \{3,4\} \wedge x_3 \notin \{1,3\} \Rightarrow x_3 \notin \{1,3,4\} \Rightarrow x_3=2$

Constraint 6: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_3,x_4)$

Deduction: $x_3=2 \Rightarrow x_4 \notin \{1,2,3\}$

Deduction: $x_4 \notin \{1,2,3\} \wedge x_4 \notin \{1,4\} \Rightarrow x_4 \notin \{1,2,3,4\}$

Therefore, with no possible value to assign to $x_4$, $x_1=1$ is not going to work as a solution, return failure, and backtrack

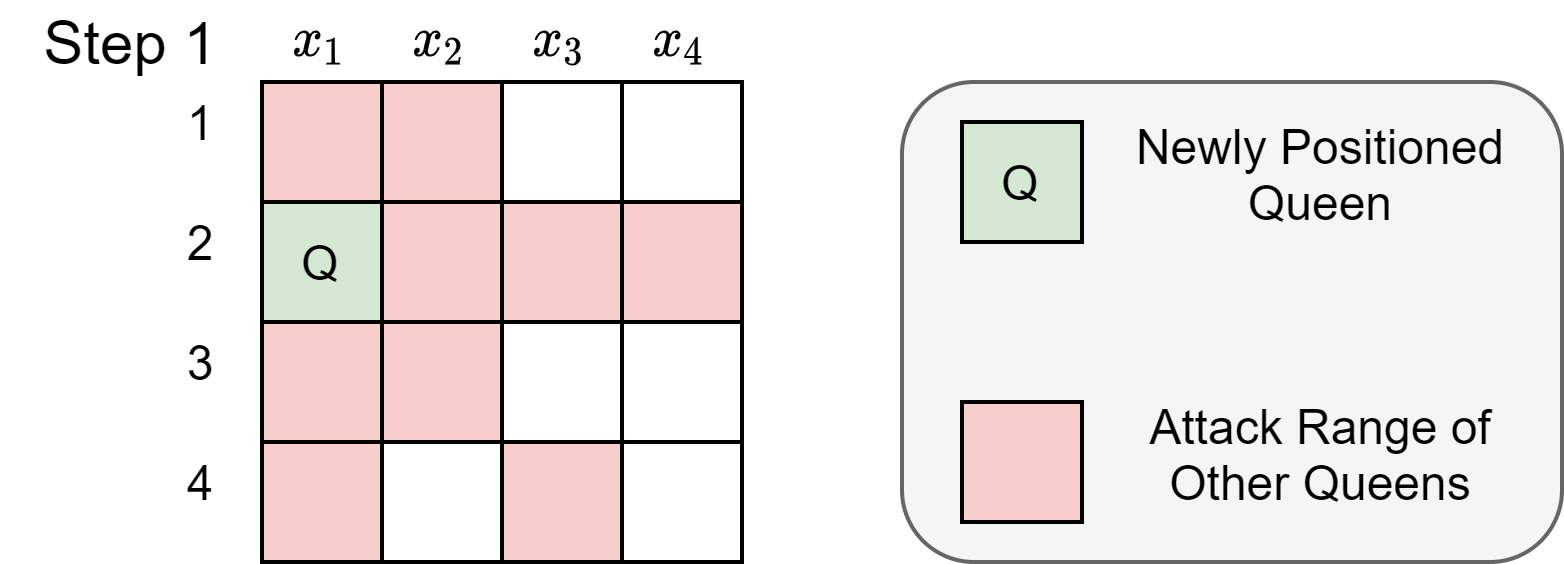

Inference Function Logic at Step 5

At step 5, because $x_1=2$, the inference function can deduce that the red squares in Figure 4 are within a queen’s attacking range and no other queens can be placed there.

|

|---|

| Figure 4: Board state at various steps of improved BacktrackingSearch with Inference |

Then, the inference function looks at each and every constraint to infer restrictions on the rest of the variables.

Constraint 1: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_2)$

Observation from Figure 4 : $x_1=2 \Rightarrow x_2 \notin \{1,2,3\} \Rightarrow x_2=4$

Constraint 2: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_3)$

Observation from 4 : $x_1=2 \Rightarrow x_3 \notin \{2,4\}$

Constraint 3: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_4)$

Observation from 4 : $x_1=2 \Rightarrow x_4 \notin \{2\}$

Constraint 4: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_2,x_4)$

Deduction: $x_2=4 \Rightarrow x_4 \notin \{2,4\}$

Deduction: $x_4 \notin \{2,4\} \wedge x_4 \notin \{4\} \Rightarrow x_4 \notin \{2,4\}$

Constraint 5: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_2,x_3)$

Deduction: $x_2=4 \Rightarrow x_3 \notin \{3,4\}$

Deduction: $x_3 \notin \{3,4\} \wedge x_3 \notin \{2,4\} \Rightarrow x_3 \notin \{2,3,4\} \Rightarrow x_3=1$

Constraint 6: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_3,x_4)$

Deduction: $x_3=1 \Rightarrow x_4 \notin \{1,2\}$

Deduction: $x_4 \notin \{1,2\} \wedge x_4 \notin \{2,4\} \Rightarrow x_4 \notin \{1,2,4\} \Rightarrow x_4=3$

Therefore,the function returns $\{x_2=4, x_3=1, x_4=3\}$

Therefore, the Backtracking search with an inference function, Algorithm 3, becomes much more efficient. The overall efficiency, however, is now strongly dependent on the efficiency of the Infer function, which can be very costly to implement. Now, the important question is How do you implement the Infer functions? Let us discuss important questions related to functions:

Representation of data structure: It stores each of the variables $x_i$ and a set of values that $x_i$ is not supposed to take; such a set of values grows as Infer makes deductions based on the current assignment and constraints. For example: $x_1 \notin\{1,2\}, x_2 \notin \{1,3,4\}\ldots$.

Store the constraints: The naive approach to store the constraints could be storing them as a truth table described in Table 1, but we know that it is not efficient to use truth tables for larger data; hence, the more efficient way of storing the constraints is to come up with some function that can return true/false depending on the current values of the argument variables. Definitions of such a function depend on the application; for example, for the n-Queen problem, such a function can be $f(x_1,x_2) \{ if \{|val(x_1)-val(x_2)| > 1\} \; \text{return True else False} \}$.

ComputeDomain $(x, \mathsf{assign},\mathsf{inference})$: In addition to the above-discussed questions, we also need a way to compute the domain of a variable $x$ given an assignment and inference. We use the function ComputeDomain $(x, \mathsf{assign},\mathsf{inference})$ to return the domain of variable $x$ given assignment and inference. Again, the definition of the ComputeDomain function is not fixed and mainly depends on the application and inference definition. For example: if we have the assignment, $\{x_1 = 1\}$ and the inference, $\{x_1 \notin \{2,3\}\}$, then the ComputeDomain $(x_1, \mathsf{assign},\mathsf{inference})$ should output the domain of $x_1$ as $\{1\}$. In another example for the assignment, $\{x_2 = 1\}$ and the inference, $\{x_1 \notin \{2,3\}\}$ the ComputeDomain $(x_1, \mathsf{assign},\mathsf{inference})$ should output the domain of $x_1$ as $\{1,4\}$.

Algorithm 4 represents the function of Algorithm 3.

Algorithm 4 Infer $(\mathsf{prob},\mathsf{var},\mathsf{assign})$ function of Algorithm 3

- $\mathsf{inference} \gets \emptyset$

- $\mathsf{varQueue} \gets [\mathsf{var}]$

- while $\mathsf{varQueue}$ is not empty do

- $~~~~$ $ y \gets \mathsf{varQueue}$.pop()

- $~~~~$ for each constraint $C \in \mathsf{prob}$ where $y \in Vars (C)$ do

- $~~~~~~~~~~$ for all $x \in Vars(C) \setminus y$ do

- $~~~~~~~~~~~~$ S $\gets$ ComputeDomain $(x, \mathsf{assign},\mathsf{inference})$

- $~~~~~~~~~~~~$ for each value $v \in S$ do

- $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ if no valid value exists $\forall \mathsf{var} \in Vars(C) \setminus x$ s.t. $C[x = v]$ is satisfied then

- $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ $\mathsf{inference} \gets \mathsf{inference} \cup (x \not \in {v})$

- $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ $T \gets$ ComputeDomain $(x,\mathsf{assign},\mathsf{inference})$

- $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ if $T = \emptyset$ then return $\mathsf{failure}$

- $~~~~~~~~~~~~~~$ if $S \neq T$ then $\mathsf{varQueue}.add(x)$

- return $\mathsf{inference}$

Example in n-Queen problem

Recall in the n-Queen problem for Algorithm 4, at the start of the execution of the algorithm, the assignment $x_1=1$ was made, and the inference function is then called on this assignment.

$x_1$ is pushed and popped, and all the constraints in the problem involving variable $x_1$ are iterated over a for loop, namely: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_2),\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_3),\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_4)$.

For the first constraint $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_2)$ to be iterated, the inner for loop calls upon $x$ in the constraint that is not $x_1$, which in this case is only $x_2$. The initial domain for $x_2$ stored in $S$ is $\{1,2,3,4\}$. For each value in $S$, we check if there is a valid value for $x_2$ so that $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_2)$ is satisfied. In this case, the domain of $x_1$ is $1$ because it has already been assigned that value. For example, when $x_2=2$, no valid value for $x_1\in \{1\}$ exists so that the constraint is satisfied, therefore, $x_2\notin \{1\}$ is added into inference. The same is done $x_2=2$ and $x_2\notin \{2\}$ is added to inference. However, there are no inconsistencies for $x_2\in{3,4}$, so those are not added into inference. After that, the domain for $x_2$ is computed again with the updated inference, which returns set $T$ as $x_2\in\{3,4\}$, which is not an empty set, but is also not the same as $S$. Thus, $x_2$ is added into $\mathsf{varQueue}$.

The same process is iterated for the other remaining constraints to add values of $x_3$ and $x_4$ into $\mathsf{inference}$.

When $x_2$ is popped from the $\mathsf{varQueue}$, all the constraints in the problem involving variable $x_2$ is iterated over a for loop, namely: $\mathsf{noattack}(x_1,x_2)$, $\mathsf{noattack}(x_2,x_3)$, $\mathsf{noattack}(x_2,x_4)$.

For example’s sake, let us consider constraint $\mathsf{noattack}(x_2,x_3)$. The inner for loop then calls upon $x$ in the constraint that is not $x_2$, which in this case is only $x_3$. The initial domain for $x_3$ stored in $S$ is $\{2,4\}$. For each value in $S$, we check if there is a valid value for $x_3$ so that $\mathsf{noattack}(x_2,x_3)$ is satisfied. For example, when $x_3=4$, no valid value of $x_2\in \{3,4\}$ exists so that $\mathsf{noattack}(x_2,x_3)$ is satisfied, so $x_3\notin \{4\}$ is added into the constraint. However, $x_3=4$ has no inconsistencies, so it is not added to inference. After that, the domain for $x_3$ is computed again with the updated inference, which returns $T$ as $x_3\in\{2\}$, which is not an empty set, but is also not the same as $S$. Thus, $x_3$ is added into $\mathsf{varQueue}$.

The algorithm continues on until it reaches constraint $\mathsf{noattack}(x_3,x_4)$, where the $T$ for $x_4$ is an empty set, thus returning failure to the main backtracking algorithm.

Alternative Implementation of Inference

The computation required for the Infer function can be expensive and may potentially slow down the search. Some alternative implementations attempt to limit the depth of the inference in order to reduce computational cost. However, one important point to note here is this would also mean that the backtracking algorithm does not benefit from information that can be derived from deeper levels of inference.

The alternative implementations are as follows:

- Don’t add any variable to $\mathsf{varQueue}$ at each iteration. This is the equivalent of deleting Line 13 of the Algorithm 4.

- This ensures that the inference will rule out only some values of the variable.

- This variant of inference is also known as Forward Checking.

- Although forward checking can rule out many inconsistencies, it does not infer further ahead to ensure arc consistency for all the other variables.

- Replace the $S\neq T$ condition in Line 13, replace with $|T|=1$.

- This goes one step further from forward checking and allows for further inferences for the variables that have one valid value in the domain.

- Depending on the complexity of the application, the condition can be set to any particular value, e.g., $|T|\leq 3$.

In addition to the aforementioned different variants of implementation, there are many heuristics that are proven to be efficient in backtracking search algorithms.

Minimum Remaining Value Heuristic: In the PickUnassignedVar function of the backtracking search, always choose the next unassigned variable that has the smallest domain size. The idea behind this heuristic is to assign values to variables that are most likely to cause failure quickly, thus allowing for the pruning of larger branches in the search tree.

Least Constraining Value Heuristic: In the OrderDomainValue function of the backtracking search, always pick a value in the domain that rules out the least domain values of other neighboring variables in the constraint. This allows for the maximum flexibility for subsequent variable assignments. This heuristic is only relevant if we are interested in a single solution. If we want to find all (multiple) solutions to the problem, then all values for an assignment to a variable will be iterated through in any case. Thus, it is not relevant here.

How Hard is the Constraint Satisfaction Problem?

Nevertheless, the ways described are only heuristics and are not guaranteed to perform well in any kind of problem. CSPs are very hard to solve, belonging to a set of problems known in Computer Science as NP-complete, where there are no Polynomial time solutions to solve these problems, but the answer to these problems can be checked in polynomial time. There are multiple variants of CSPs, and while most are NP-complete, some can be solved in Polynomial time. Below are some variants of CSPs.

There are some special variants of CSP, as listed below:

- Binary CSP: Every constraint is defined over two variables(NP-complete).

- Boolean CSP(SAT): The domain of every variable is 0,1 (NP-complete).

- 2-SAT: Combination of Binary CSP and Boolean CSP, that is, every constraint is defined over two variables, and the domain of every variable is 0,1 (Polynomial-time (P)-solvab