Knowledge Representation and Reasoning

Knowledge

What is knowledge? According to Wikipedia:

Knowledge is familiarity, awareness, or understanding of someone or something, such as facts, information, description, skills which is acquired through experience or education by perceiving discovering or learning.

We can all agree that this is a very complicated definition. One widely accepted definition by philosophers is,

Knowledge is knowing something to be true.

But, again, what does it mean to know something to be true? For a statement to be true, it has to meet following three criteria:

- The person believes the statement to be true.

- The statement is in fact true.

- The person is justified in believing the statement to be true.

Considering the following sentences:

- John knows that Mary will come to the party.

- John believes that Mary will come to the party.

The word “believes” is used to show that John is not completely certain about Mary coming to the party. In this course, we will not distinguish between belief and truth, that is between criteria (1) and (2).

Now, let us move our attention towards, “justification”. The question here is, how do we justify that something is true ?

Aristotle is usually credited among Greek philosophers to recognize that reasoning or justification is about form. One of his famous syllogism:

All Greeks are human.

All humans are mortal.

All Greeks are mortal.

But, it turns out that the justification is not only about the form of the sentences. Considering the following example:

Not all Greeks are human.

Not all human are mortal.

Not all Greeks are mortal.

[This is not correct.]

Almost 2000 years later, Boole realized that the statements are about the class of objects and his idea was to use symbolic variables. Boole’s idea was to replace “Greeks” by $p$, “humans” by $q$, and “mortal” by $r$. Then, we essentially have:

If p then q (p ⇒ q)

If q then r (q ⇒ r)

If p then r (p ⇒ r)

$p$, $q$, and $r$ are symbolic variables. A symbolic variable reflects some underlying quantity, which at this point is unknown. The possible values of these symbolic variables are the truth values.

At this point, let us first answer the important question that everyone of you must be thinking, “how does all of these relates to AI?”

Alan Turing first proposed the term “Machine Intelligence”. In 1958, John McCarthy pro-posed in his paper “Programs with Common Sense”, to use formal logic to represent information in computers. According to McCarthy’s paper, a program has common sense if it automatically deduces for itself a sufficiently wide class of immediate consequences of anything it is told and what it already knows.

|

|---|

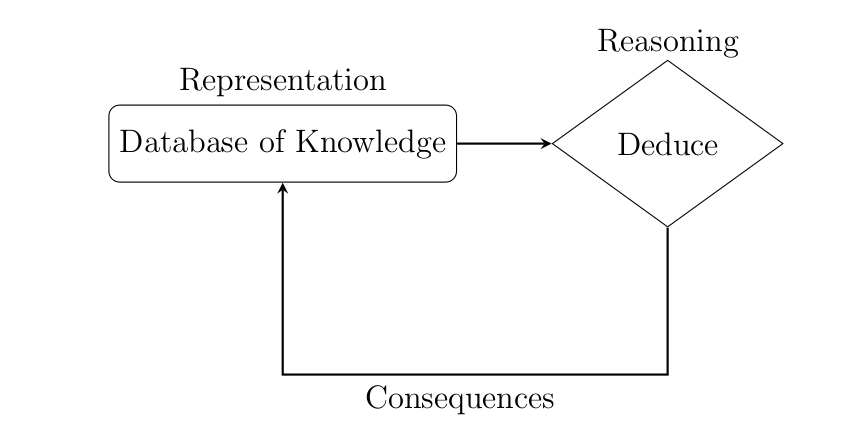

| Figure 1: Programs with common sense |

Figure 1 represent a program with common sense in a AI system looks like. As shown in Figure 1, a knowledge-based system is able to make deductions from its database of knowledge. The deduction can then be added back to the database to be used for further deductions.

In this module, we will focus on the two boxes shown in Figure 1.

- How do we represent, what the system knows?

- How do we deduce the consequences?

Propositional Logic: Syntax and Semantics

In the previous section, we had discussed about symbolic variables and the usage of symbolic variables. Let us call them as propositional variables. A propositional variable is either true or false. We want to abstract away the arguments about whether certain things in the world are true, whether Crazy Rich Asians is a good movie or sky is blue. We can represent them with a proposition $p$ and then that proposition can take value true or false.

Syntax

The first question concerns that, what should we assign a variable?. Let us consider the following the sentences:

- If taxi arrives on time then John and Mary will be at party.

- If John and Mary are at party then Jack is at party.

- If John is at party then Jack is at party.

What should we assign variables to represents the above mentioned sentences? Let us try to link this to object oriented programming, where we need to figure about what attributes do we want to have an object for. Similar to that, we assign propositional variables to all the “relevant” objects, their attributes and relationship,like:

- Man, Women, Student, Adult

- Mortal, Genius, Rich, Crazy

- Friends(John, Jack), Lovers(Romeo, Juliet)

Now, we have subject/object, but we also need verbs and punctuation. That is, to build a language from scratch, we need 3 component:

- word: We use proposition. Propositions are statements that are true or false but not both. We denote PROP be the universal set of all propositions.

- verb:

- Unary: “$\lnot$”.

- Binary: “$\lor$”, “$\land$”, $\ldots$

Henceforth, we use $\odot$ to represent binary operators.

- punctuation: {”(“,”)” }

Well Formed Formula (WFF)

As we have all 3 component of our language, called propositional logic. Let us now try to frame a statement in our language. \(\begin{align*} &\mathsf{FORM}_{0} = \mathsf{PROP}\\ &\mathsf{FORM}_{i+1} = \mathsf{FORM}_{i} \cup \{ (\lnot \varphi); \varphi \in \mathsf{FORM}_{i} \} \cup \{ (\alpha \odot \beta); \alpha, \beta \in \mathsf{FORM}_{i}\}\\ &\mathsf{FORM} = \cup_{i=0}^{\infty} \mathsf{FORM}_{i} \end{align*}\)

$\mathsf{FORM}$ is called a well-formed formulas (WFF). $\mathsf{FORM}$ defines all possible entries in our propositional logic.

For example: $(( p \lor q) \lor r)$, $(\lnot (p \lor q))$.

Parsing of WFF Human languages often contain a lot of ambiguity, an example is the following valid English sentences:

- We saw her drunk.

- Every farmer who owns a donkey beats it.

- Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo

The above sentence is grammatically correct, but they all have multiple meanings associated with it. To avoid such ambiguity in propositional logic, we need further need to formalizes the formulas:

Formulas are either atomic or composite.

- The set of atomic formulas: $\mathsf{PROP}$.

For a composite formula ($\lnot \varphi$).

- $\lnot$ is the primary connective.

- $\varphi$ is the immediate sub formula.

For a composite formula ($\psi \odot \varphi$).

- $\odot$ is the primary connective.

- $\psi$ and $\varphi$ are immediate sub formulas.

Theorem [Unique Readability] Every composite formula $\varphi$ has a unique primary connective and well-formed sub formulas.

The important thing to notice here is, every composite formula has a unique ordering of primary connectives and a unique set of immediate sub-formulas.

Consider the example: $((p \land q) \lor r)$. Primary connective: $\lor$, Immediate sub-formulas $(p \land q)$.

Semantics

We had propositions to capture possible worlds, but how do we talk about a particular world? Consider this example: She was the best software engineer the company ever had. Is this sentence true or false ? To give judgment about the sentence, we need to know who are we referring to in “she”, “the company”. Therefore, the question here is, *How do we capture different worlds?}.

Let us consider an example $\varphi:=$ The table is rectangular. Let us assume, we have a function $\tau$ that maps “The table” to your classroom’s table. That is, $\tau$ exactly capture the world “the table”, now can you identify whether $\varphi$ is true or not? Let us try to formalize this:

(Definition) $\tau$ is a function that maps the $\mathsf{PROP}$ to ${0,1}$, or $\tau \in 2^{\mathsf{PROP}}$.

(Definition) Formula $\varphi$ is also a function that maps the $2^{\mathsf{PROP}}$ to ${0,1}$, or $\varphi \in 2^{2^{\mathsf{PROP}}}$.

Consider an example: $\mathsf{PROP}$ = ${p,q}$, $\varphi:= (p \lor q)$, and $\tau:= {p \vdash 1, q \vdash 0}$, then $\varphi(\tau) := (1 \lor 0) = 1$. Again, notice that we can consider operators $\lnot, \land, \lor, \ldots$ as a functions. $\lnot: {0,1} \mapsto {0,1}$, $\land: {0,1}^2 \mapsto {0,1}$.

That is,

\[\begin{equation} \varphi(\tau) := \begin{cases} \tau(p) & \text{if } \varphi = p \in \mathsf{PROP}\\ \lnot (\alpha(\tau)) & \text{}\\ \odot(\alpha(\tau),\beta(\tau)) & \text{} \end{cases} \end{equation}\]Let us consider another example, $\varphi := ((p \lor q) \land r)$.

\[\begin{align*} \varphi(\tau) &:= \land((p \lor q)(\tau), r(\tau)) \\ &:= \land(\lor(p(\tau),q(\tau), r(\tau))) \end{align*}\](Definition) A truth assignment $\tau$ satisfies formula $\varphi$ if and only if $\varphi(\tau)$ is $1$. We will use symbol $\models$, and say $\tau \models \varphi$ if and only if $\varphi(\tau) = 1$. If such a $\tau$ exists then we say $\varphi$ is satisfiable.

(Definition) A formula $\varphi$ is considered to be valid if for all $\tau$ in $2^{\mathsf{PROP}}$, $\varphi(\tau)$ is $1$. We use the notation $\models \varphi$, that is, $\models \varphi \iff \underset{\tau \in 2^{\mathsf{PROP}}}{\forall} \varphi(\tau) = 1$. Example: $p \lor \lnot p$.

(Definition) A formula $\varphi$ is considered to be unsatisfiable if there does not exists a $\tau$ in $2^{\mathsf{PROP}}$ such that $\varphi(\tau)$ is $1$. We use the notation $\not \models \varphi$, that is, $\not \models \varphi \iff \underset{\tau \in 2^{\mathsf{PROP}}}{\forall} \varphi(\tau) = 0$. Example: $p \land \lnot p$.

Observe that if $\varphi$ is unsatisfiable, then $(\lnot \varphi)$ is valid.

First Order Logic

In normal speaking we could use logic to say something like: If all humans are mortal (say , $\alpha$) and all Greeks are human (say, $\beta$) then all Greeks are mortal (say, $\gamma$). Therefore, if we have $\alpha$ = (H$\implies$ M) and $\beta$ = (G $\implies$ H) and $\gamma$ = (G$\implies$ M) (where H, M, G are propositions), we could say that (($\alpha \wedge \beta$) $\implies \gamma$) is valid.

This is good because it allows us to focus on a true or false statement about one person. This kind of logic (propositional logic) was adopted by Boole (Boolean Logic) But what about using “some” instead of “all” in $\beta$ in the statements above? Would the statement still hold? Consider the following example:

Someone is taller than me.

I am taller than someone.

I am taller than me?

What about we want to talk about statements like,

Best friend of John is Mary

Without explicitly generating all propositions {BestFriend(John, Mary)} = 1, BestFriend(John, Jake)} = 0}. Can we represent it succinctly as {BestFriend(John) = Mary}} with an additional information that everyone has only one best friend?

Furthermore, How can we express statements like,

For every student, there exists a course that is difficult for the student.

Where students and course are not concrete things. Let us try to come up basic element to represent statement like above.

Elements of First Order Logic

- Quantifiers: $\forall, \exists$

- Variables: ${x, y, \ldots}$ which are abstract objects which can take any value, not just 0 and 1.

- Predicates: $P^{k}(t_1, \ldots, t_k): D^{k} \rightarrow {0,1}$ can take multiple arguments as inputs and always return true or false. $Brother(John, Jake)$ is a $2$-ary predicate. (Propositions are $0$-ary predicates)

- Functions: $f^{k}(t_1, \ldots, t_k): D^{k} \rightarrow D$ can return any value. \ A k-ary function is denoted as $f^{(k)}$. A 2-ary predicate is $f^{2}(x_1,x_2)$

Semantics of First Order Logic

Consider the formula, $>(+(x, 2), 3)$ where $>$ is a predicate, $+$ is a function, $x$ is a variable and $2, 3$ are 0-ary functions. In order to evaluate this formula, an interpretation for the functions and predicates is required. Furthermore, a domain of values must also be defined. To define, we need the help of a mathematical structure, $\mathcal{A}$, which is expressed as: \(\mathcal{A} = (\mathcal{D}, f_1^{k, A}, f_2^{k, A}, \dots, P_1^{k, A}, \dots)\)

When considering the assignment of values, it is important to first consider the mappings of predicates and functions:

\[\begin{align*} f^{k}&: \mathcal{D}^k \rightarrow \mathcal{D} \\ P^k &: \mathcal{D}^k\rightarrow \{0, 1\} \end{align*}\]Next, the functions must be defined such that it assigns values to the variables and terms in the formula. Consider the statement $A\models (x = 2)$. Does it make sense to ask whether the formula $x=2$ is true in the world $A$? The truth of the formula depends on the value of $x$, but $x$ is a variable and can take any value. Some values of $x$ might make the formula true, while others might falsify it. Thus, we need to qualify our answer by saying that the formula is true when $x$ has a certain value. To do this, we can use a function $\alpha$ that assigns values to variables. Such a function, $\alpha$, is called a `binding’. Thus, statements about semantics have the form $A,\alpha \models \phi$ where $A$ is a structure, $\phi$ is a formula and $\alpha$ is a variable assignment, i.e., $\alpha:\mathsf{Vars} \rightarrow \mathcal{D}$. Note that our notion of truth is now a ternary relation, as opposed to the binary relation of propositional logic.

Let us now define above mentioned notion formally. First, we need to extend the notion of bindings to terms. (Definition) Given structure $A$ and $\alpha:\mathsf{Vars} \rightarrow \mathcal{D}$, we define $\overline{\alpha}:\mathsf{Term} \rightarrow \mathcal{D}$ as follows:

- $\overline{\alpha}(x) = \alpha(x)$, where $x$ is a variable

- $\overline{\alpha}(f(t_1,\dotsc,t_k)) = f^A(\overline{\alpha}(t_1),\dotsc,\overline{\alpha}(t_k))$, where $k$ is the arity of $f$, and $t_1, \ldots, t_k \in \mathsf{Term}s$.

Note that if $f$ is a $0$-ary function then $\overline{\alpha}(f) =f^A$.

We can think of an assignment as an array. If $\alpha(x_i)=a_i$, an assignment to $x_1,\ldots,x_n$ is the array $[a_1,\ldots,a_n]$. Therefore, $\alpha[x_i\mapsto a’_i]$ simply updates the $i$th entry of the array.

\[\begin{align*} \alpha &: \mathsf{Vars} \rightarrow \mathcal{D} \\ \bar{\alpha} &: \mathsf{Term} \rightarrow \mathcal{D} \\ \end{align*}\]The assignment of $\bar{\alpha}(f^k(t_1, \dots t_k))$ can evaluated as follows: \(\begin{align*} \bar{\alpha}(f^k(t_1, \dots t_k)) = f^k(\bar{\alpha}(t_1), \dots \bar{\alpha}(t_k)) \end{align*}\)

Semantics relates the syntax to the world (relational structure). $A\models \phi$ denotes that formula $\phi$ is true in the world $A$. Here `$\models$’ is the semantical relation.

Satisfiability of First Order Logic

Now that a mathematical structure and a function for the assignment have been defined, satisfiability can now be considered. Let’s consider the different possible formulas for satisfiability given $\mathcal{A}$ and $\alpha$.

- $\mathcal{A}, \alpha \models P^k(t_1, \dots, t_k) \leftrightarrow P^k(\bar{\alpha}(t_1), \dots, \bar{\alpha}(t_k)) = 1$

- $\mathcal{A}, \alpha \models (\varphi \lor \psi) \leftrightarrow (\mathcal{A}, \alpha \models \varphi) \lor (\mathcal{A}, \alpha \models \psi)$

- $\mathcal{A}, \alpha \models (\varphi \land \psi) \leftrightarrow (\mathcal{A}, \alpha \models \varphi) \land (\mathcal{A}, \alpha \models \psi)$

- $\mathcal{A}, \alpha \models (\lnot \varphi) \leftrightarrow \mathcal{A}, \alpha \not\models \varphi$

- $\mathcal{A}, \alpha \models \exists x \varphi \leftrightarrow \exists v \in \mathcal{D}: \mathcal{A}, \alpha[x \mapsto v] \models \varphi$

- $\mathcal{A}, \alpha \models \forall x \varphi \leftrightarrow \forall v \in \mathcal{D}: \mathcal{A}, \alpha[x \mapsto v] \models \varphi$

Let us consider $\varphi = (x < 2) \land (\exists x: ((x + 2) > 3))$ where $\mathcal{A} = (\mathbb{N}, <^\mathcal{A}, \dots)$ and $\alpha[x] = 1$. It can be seen that $\mathcal{A}, \alpha \models \varphi$ as $(x < 2)$ is satisfied with this assignment of $x$, whereas $(\exists x: ((x + 2) > 3))$ can be satisfied by overriding $\alpha[x]$ with another value that satisfies this equation. Therefore, it is possible that $\varphi$ is satisfiable.

Free and Bound Variables

For any first order logic, $\phi$, let $\mathsf{FVars}(\varphi) \in 2^{\mathsf{Vars}}$ denote the set of free variables of $\varphi$. Let us recursively define $\mathsf{FVars}(t)$ for any term $t \in \mathsf{Term}$, and $\mathsf{FVars}(\varphi)$:

- For any $x \in \mathsf{Vars}$, $\mathsf{FVars}(x) = {x}$.

- For any $f \in \mathsf{Functions}$, $\mathsf{FVars}(f(t_1,…,t_{k_f})) = \bigcup_i \mathsf{FVars}(t_i)$. This covers all terms.

- For any $P \in \mathsf{Predicate}$, $\mathsf{FVars}(P(t_1,…,t_{k_P})) = \bigcup_i \mathsf{FVars}(t_i)$.

- $\mathsf{FVars}(\neg \varphi) = \mathsf{FVars}(\varphi)$.

- For any logical connective $\circ$, $\mathsf{FVars}(\alpha \circ \beta) = \mathsf{FVars}(\alpha) \cup \mathsf{FVars}(\beta)$.

- For any quantifier # $ \in {\forall, \exists}$ and variable $x \in \mathsf{Vars}$, $\mathsf{FVars}($# $x : \varphi) = \mathsf{FVars}(\varphi) \setminus {x}$.

[Theorem] Relevance Lemma for first order logic Fix the structure $\mathcal{A}$. Let us consider a formula $\varphi$. Let $\alpha_1, \alpha_2 \in \mathcal{D}^{\mathsf{Vars}}$ be two variable assignments on $\mathcal{A}$. If for all $x \in \mathsf{Vars}$, $\alpha_1[x] = \alpha_2[x]$, then $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_1 \models \varphi$ iff $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_2 \models \varphi$.

Proof. By induction on $\mathsf{Term}$ then on $\mathsf{Form}$.

For any $x \in \mathsf{FVars}(\varphi)$, $\bar{\alpha_1}(x) = \alpha_1(x) = \alpha_2(x) = \bar{\alpha_2}(x)$.

For any $f \in \mathsf{Functions}$ that appears in $\varphi$, $\bar{\alpha_1}(f^\mathcal{A}(t_1,…,t_{k_f})) = f^\mathcal{A}(\bar{\alpha_1}(t_1),…,\bar{\alpha_1}(t_{k_f})) = f^\mathcal{A}(\bar{\alpha_2}(t_1),…,\bar{\alpha_2}(t_{k_f})) = \bar{\alpha_2}(f^\mathcal{A}(t_1,…,t_{k_f}))$. This covers all terms.

For any $P \in \mathsf{Predicate}$ that appears in $\varphi$, $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_1 \models P(t_1,…,t_{k_f})$ iff $1 = P^\mathcal{A}(\bar{\alpha_1}(t_1),…,\bar{\alpha_1}(t_{k_f})) = P^\mathcal{A}(\bar{\alpha_2}(t_1),…,\bar{\alpha_2}(t_{k_f}))$ iff $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_2 \models P(t_1,…,t_{k_f})$.

$\mathcal{A}, \alpha_1 \models (\neg \psi)$ iff $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_1 \not \models \psi$ iff $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_2 \not \models \psi$ iff $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_2 \models (\neg \psi)$.

For any logical connective $\circ$, $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_1 \models (\beta \circ \gamma)$ iff $(\mathcal{A}, \alpha_1 \models \beta) \circ (\mathcal{A}, \alpha_1 \models \gamma)$ iff $(\mathcal{A}, \alpha_2 \models \beta) \circ (\mathcal{A}, \alpha_2 \models \gamma)$ iff $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_2 \models (\beta \circ \gamma)$.

For any variable $x \in \mathsf{Vars}$, $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_1 \models (\forall x : \varphi)$ iff [for all $v \in \mathcal{D}$, $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_{1,x \mapsto v} \models \varphi$] iff [for all $v \in \mathcal{D}$, $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_{2,x \mapsto v} \models \varphi$] iff $\mathcal{A}, \alpha_2 \models (\forall x : \phi)$. Similar for $\exists$.

In general, we do not even need the structures $\mathcal{A}$ paired with $\alpha_1$ and $\alpha_2$ to be the same; we simply need $\mathcal{A}_1$ and $\mathcal{A}_2$ to agree on the meaning of all the functions and predicates appearing in $\varphi$.

Let $\mathcal{A}$ be given. For any formula $\varphi$,

- $\varphi$ is satisfiable, if there exists a variable assignment $\alpha$ such that $\mathcal{A},\alpha \models \varphi$.

- $\varphi$ is valid, if for all variable assignments $\alpha$, $\mathcal{A},\alpha \models \varphi$. We also call $\varphi$ a sentence.

- $\varphi$ is unsatisfiable, if for all variable assignments $\alpha$, $\mathcal{A},\alpha \not \models \varphi$.

Relavance of Logic in AI

At this point, you might wonder, how are these elements connected to our AI course? Within the scope of artificial intelligence, it’s essential to encode knowledge in a specific format, where you can get answers fo your queries efficiently. You want to create a knowledge base (KB), and want to make queries like whether the KB logically entails a given formula $\varphi$. First-order logic is a powerful tool to encode the knowledge base. For example, databases can be regarded as instances of first-order logic representations.

Specifically, often we are interested in $\varphi \models \psi$, where both $\varphi$ and $\psi$ represent formulas, the underlying question is whether the models that satisfy $\psi$ also satisfy $\varphi$, that is, whether $\mathsf{models}(\varphi) \supseteq \mathsf{models}(\psi)$? In the remaining part we’ll learn how to solve these kind of queries in propositional and first-order logic.

Resolution Refutation

Resolution: $(p \lor \alpha)\land (\lnot p \lor \beta) \iff (\alpha \lor \beta)$

Let $\varphi = (p \lor \alpha)\land (\lnot p \lor \beta)$, and $\psi = (\alpha \lor \beta)$. Observe that $\varphi$ and $\psi$ are not equivalent, however $\varphi$ is satisfiable if and only if $\psi$ is satisfiable, formulas $\varphi$ and $\psi$ are called equisatisfiable formulas. The real benefit of resolution is if we somehow know that $(\alpha \lor \beta)$ is unsatisfiable then $(p \lor \alpha)\land (\lnot p \lor \beta)$ is also unsatisfiable.

Resolution is a powerful rule used in logical proofs, especially for determining unsatisfiability within propositional logic. Here, we are interested in a specific form of formulas, that is called the Clausal forms. Clause is a disjunction of literals. Literals are an atomic formula or the negation of an atomic formula.

The essence of resolution is to use pairs of clauses that contain complementary literals, eliminating these literals to form a new clause. This process is repeated, aiming to derive an empty clause, which indicates a contradiction, thus proving unsatisfiability.

To illustrate, consider the clauses derived from $\varphi = (p \lor \alpha) \land (\lnot p \lor \beta)$:

- $ c_1 = p \lor \alpha $

- $ c_2 = \lnot p \lor \beta $

Applying resolution to $c_1$ and $c_2$:

- We notice that $c_1$ contains $p$ and $c_2$ contains $\lnot p$. By resolving on $p$, we eliminate $p$ and $\lnot p$, combining the remaining parts of $c_1$ and $c_2$ to produce a new clause: $ \alpha \lor \beta $ This new clause, $ c_3 $, is derived from $c_1$ and $c_2$ by the resolution rule.

In resolution proofs, each clause $c_i$ is derived from earlier clauses $c_{i1}$ and $c_{i2}$ (where $i_1, i_2 < i$) through the resolution process. The goal is to continue this process until the derived clause is the empty clause, symbolizing a contradiction. This means the original set of clauses is collectively unsatisfiable. The process of continuously applying resolution helps in systematically exploring the implications of the initial clauses, leading effectively to a proof by contradiction if a contradiction (empty clause) is indeed derivable. Therefore, the application of resolution in clausal forms essentially transforms the problem of proving the unsatisfiability of a formula into a problem of deriving an empty clause through successive resolutions. If we can derive this empty clause, it confirms that our original assumption (the satisfiability of the formula) must be false.

Resolution over First order logic:

In the case of propositional logic we were performing resolution over propositions. In FOL, the equivelent of propositions are the predicates. Therefore, it is more complicated to perform resolution over it. Let’s consider the following case over propositional logic:

(α(x)∨¬P(y))∧(P(y)∨β(z))

(α(x)∨β(z))

That was easy to follow. Now what happens if we add quantifiers to this? Can we say a similar statement like the two below?

∀x(α(x)∨¬P(y))∧(P(y)∨β(z))

∀x(α(x)∨β(z))

Or,

∃x(α(x)∨¬P(y))∧(P(y)∨β(z))

∃x(α(x)∨β(z))

For the first case, it is easy to follow that it will hold, can we say the same for the second too? The domain itself can be very large, possibly infinite. Can we convert the whole formula to a formula only with forall quantifiers?

We want to eliminate $\exists Y$ from $\forall x \exists y (P() \lor Q(x,y))$. How can we do that? The process is called Skolemization.

Skolemization

We’ll introduce a function for each variable with $\exists$ quantifier. Therefore, a formula like the following:

$\forall x [ \neg P(x) \vee ( (\forall y[\neg P(y) \vee P(f(x, y))]) \land (\exists z[Q(x, z) \vee \neg P(z)])) ]$

Will be converted to the following:

$\forall x [ \neg P(x) \vee ( (\forall y[\neg P(y) \vee P(f(x, y))]) \land ((Q(x, g(x))) \vee \neg P(g(x)))) ] $

This idea came from Thoralf Skolem back in 1920s. Once we convert everything to forall variables, we can apply resolution to prove things.

Bonus Material

We were looking at formulas at clausal form. Now, let’s say we have a formula in a different form. In this case, we convert the formula to clausal form by some technique known as the Tseitin encoding.